Algorithms and Data Structures

Algorithms, Object Oriented Programming, Data Structures and Software Engineering

what are the main things a developer should be familiar with, in order to make an efficient software?

• Efficient Algorithms to perform tasks

• data Structures to hold and manipulate data

• OOPS to make a secure, stable, scalable and reusable code

• Software Engineering to do above said tasks in the best possible way

Data Structures

Data Structures are the abstract or virtual data holding containers which define a scheme for how to store data in memory and process it. There already exist many data structures like linked lists, stacks, queues, trees, graphs and many more. A data structure must be chosen wisely by keeping in mind the complexity and type of data to store and the data manipulations and operations to be performed on it. Data structures are ways in which data is arranged in your computer’s memory (or stored on disk). And Algorithms are the procedures, a software program uses to manipulate the data in these structures.

Algorithms

An algorithm in layman’s terms is a set of stepwise instructions written in a simple easy to understand ways to perform any complex task efficiently. In computer field these instructions follow some conventions and rules also. These English written instructions are later on converted into compatible source code using a programming language and suitable editors.

OOPS

Object Oriented Programming Struct is the latest software design methodology which emerged due to the rising incapability of structural or procedural designing techniques to handle large and complex problems. OOPS changed the way a programmer looks at the problem now. Instead of considering operations for software development, OOPS design process focus on the data and then the operation to be performed on it. OOP relates the problem at hand with the actual reality and real objects having own properties and functions. Objects and classes play an important role in implementing object orientation. Object oriented programming (OOP) offers compelling advantages over the old-fashioned procedural approach, and is quickly replacing it for serious program development.

Objects in a Nutshell The idea of objects arose in the programming community as a solution to the problems with procedural languages. An object contains both methods and variables. A class is a specification—a blueprint—for one or more objects.

Software Engineering

With just Bits & Bytes - you can build entire businesses and industries over it, and that too in a virtual world, nothing physical at all. This is the beauty of Software Engineering ! Software engineering is a study concerned with designing and implementing large and complex software projects. Software engineering defines the software development phases and steps to design, develop, implement, maintain and test the software and is applicable from the very beginning of the application development process and to the end of it. Software engineering mentions the use of extensive tools to perform each task. Information gathering is the primary and most important phase of a software development process. As in each phase we are gathering information only. Like before making an application, we decide what algorithms to implement and which data structure to use and this decision is made possible only after gathering the information about all data structures and algorithms. Similarly during maintenance and testing phase also we are continuously gathering info to find errors and areas of maintenance. Software engineering is the study of ways to create large and complex computer programs, involving many programmers. It focuses on the overall design of the programs and on the creation of that design from the needs of the end users. Software engineering is concerned with the life cycle of a software project, which includes specification, design, verification, coding, testing, production, and maintenance. Software engineering is rather abstract and is difficult to grasp until you’ve been involved yourself in a large project.

What happens to the code on collective application of above mentioned concepts?

When the knowledge of all of these subjects is collectively applied, we get an optimized, complete and efficient code. By optimized, complete and efficient software code I mean, that the source code is complete, almost free from bugs and errors, of lower complexity or fast (algorithms prove their point here), scalable, secure (scalability and security comes from object oriented design) and easily reusable (inheritance plays an important role in code reuse).

How to apply them collectively?

Whenever we’re given a software project or product to build we are provided with some raw information and the type of data which would be encountered while in the software development phase and also the operations and data manipulations to be done on the data. So our first step should be to choose the appropriate data structure which could easily handle the enormous amount of such data and complex operations performed on this data. In order to make operations we’ve to devise an algorithm. Mind it, an object oriented algorithm is the new trend.

But before implementing all these steps, what essentially required in prior is the research. As a famous saying in the programming world suggests: “The sooner you start to code, the longer the program will take“

So an extensive exhaustive research is always required before writing the actual code. A research to find out which data structure is the best, a research to deduct an efficient object oriented algorithm with least complexity and a research to find out how and what classes should be made and what methods/functions the objects of those classes should perform. This is done with the help of software engineering tools and concepts.

Algorithms, data structures and the object oriented struct are somewhat closely related to each other and the concepts are applied while the actual code writing process. Almost every serious programmer spend about a year on these subjects. Software engineering plays no role in writing the code as such but helps in deciding what to write i.e what algorithms to apply, which data structure to use and what parts of the program should obey object oriented rules and where to use functional or procedural programming methodologies. That is why software engineering is studied in separation to them and mostly ignored by the developers.

An introduction to data structures

This part describes about some commonly used data structures and their applications in the real programming world. So here’s the brief guide to data structures and abstract data types (ADT’s)

Computer system is mainly used as a data manipulation system. Elementary data can be represented in these forms:

• Data

• data items

• data structures

Data structures are mainly used to accomplish the following tasks on the given data:

• data representation

• data storage

• data organisation

• data processing

• data management

All these are data manipulation processes only. Data structures let us combine data of different types and process them together. It refers to a named group of data of different types which can be processed as a single unit. A data structure has well defined set of operations, behaviour and properties.

Situations in which they’re useful are classified into three categories:

• Real-world data storage

• Programmer’s tools

• Modelling

Things to keep in mind while designing a data structure:

• logical picture

• data representation method

• operations to be applied

In computer science, a data structure is a particular way of storing and organizing data in a computer so that it can be used efficiently. Different kinds of data structures are suited to different kinds of applications, and some are highly specialized to specific tasks. For example, B-trees are particularly well-suited for implementation of databases, while compiler implementations usually use hash tables to look up identifiers. Data structures are used in almost every program or software system. Data structures provide a means to manage huge amounts of data efficiently, such as large databases and internet indexing services. Usually, efficient data structures are a key to designing efficient algorithms. Some formal design methods and programming languages emphasize data structures, rather than algorithms, as the key organizing factor in software design.

Basic principles

Data structures are generally based on the ability of a computer to fetch and store data at any place in its memory, specified by an address—a bit string that can be itself stored in memory and manipulated by the program. Thus the record and array data structures are based on computing the addresses of data items with arithmetic operations; while the linked data structures are based on storing addresses of data items within the structure itself. Many data structures use both principles, sometimes combined in non-trivial ways (as in XOR linking) The implementation of a data structure usually requires writing a set of procedures that create and manipulate instances of that structure. The efficiency of a data structure cannot be analyzed separately from those operations. This observation motivates the theoretical concept of an abstract data type, a data structure that is defined indirectly by the operations that may be performed on it, and the mathematical properties of those operations (including their space and time cost).

Common data structures

Common data structures include: array, linked list, hash-table, heap, Tree (Binary Tree, B-tree, red-black tree), stack, and queue.

Language support

Most assembly languages and some low-level languages, such as BCPL, lack support for data structures. Many high-level programming languages, and some higher-level assembly languages, such as MASM, on the other hand, have special syntax or other built-in support for certain data structures, such as vectors (one-dimensional arrays) in the C language or multi-dimensional arrays in Pascal. Most programming languages feature some sorts of library mechanism that allows data structure implementations to be reused by different programs. Modern languages usually come with standard libraries that implement the most common data structures. Examples are the C++ Standard Template Library, the Java Collections Framework, and Microsoft’s .NET Framework. Modern languages also generally support modular programming, the separation between the interface of a library module and its implementation. Some provide opaque data types that allow clients to hide implementation details. Object-oriented programming languages, such as C++, Java and .NET Framework use classes for this purpose.

Data structures may be simple or compound or linear and non linear

Arrays and structure come under simple category while linked lists, stacks, queues are categorised into non-linear data structures which are of compound nature as well. Trees and graphs are also the non-linear compound data structures.

Some Common Data Structures

Arrays

Stacks A stack can be used to check whether parentheses, braces, and brackets are balanced in a computer. A stack is also a handy aid for algorithms applied to certain complex data structures. Stack plays a vital role in parsing (analysing) arithmetic expressions such as 3*(4+5). Most microprocessors use a stack-based architecture. When a method is called, its return address and arguments are pushed onto a stack, and when it returns, they’re popped off. The stack operations are built into the microprocessor. Some older pocket calculators used a stack-based architecture. Instead of entering arithmetic expressions using parentheses, you pushed intermediate results onto a stack.

Binary Trees It is used to help traverse the nodes of a tree.

Graphs Searching the vertices of a graph (a technique that can be used to find your way out of a maze).

Linked lists

Queues They’re also used to model real-world situations such as people waiting in line at a bank, airplanes waiting to take off, or data packets waiting to be transmitted over the Internet. There are various queues quietly doing their job in your computer’s (or the network’s) operating system. There’s a printer queue where print jobs wait for the Queues printer to be available. A queue also stores keystroke data as you type at the keyboard. This way, if you’re using a word processor but the computer is briefly doing something else when you hit a key, the keystroke won’t be lost; it waits in the queue until the word processor has time to read it. Using a queue guarantees the keystrokes stay in order until they can be processed.

Priority queue Like ordinary queues, priority queues are used in various ways in certain computer systems. In a preemptive multitasking operating system, for example, programs may be placed in a priority queue so the highest-priority program is the next one to receive a time-slice that allows it to execute.

Trees

Stacks, queues and priority queues are the programmer’s data srructures.

static memory allocation occurs at the compile time hence fixed size data types

dynamic memory allocation takes place during the run time hence data structures can be of variable size

contagious and non contagious memory allocation

free pool allocation

garbage collection

Algorithms + data structures = programs

Pseudocode

source code

algorithm

byte code

overflow and underflow

Abstract data type ADT can be defined as a set of values and set of operations where implementation part is hidden. ADT is a mathematical model for a certain class of data types of one or more programming language that have similar semantics.

common operations done on data structures

traversal

searching

sorting

insertion

deletion

query

Algorithms and Complexity Analysis

This part of the document describes about the commonly used algorithms a programmer must be familiar with and the concepts to construct fast and efficient algorithms for any problem.

After reading this, you will be able to distinguish between the following terms and will have a better understanding of the concept of complexity analysis and algorithms. • big O notation • asymptotic behaviour • worst-case analysis • sorting techniques and their complexities

Introduction The term analysis of algorithms is used to describe approaches to the study of the performance of algorithms. Algorithm complexity is just a way to formally measure how fast a program or algorithm runs, so it really is quite pragmatic. We already know there are tools to measure how fast a program runs. There are programs called profilers which measure running time in milliseconds and can help us optimize our code by spotting bottlenecks. While this is a useful tool, it isn’t really relevant to algorithm complexity. Algorithm complexity is something designed to compare two algorithms at the idea level — ignoring low-level details such as the implementation programming language, the hardware the algorithm runs on, or the instruction set of the given CPU. We want to compare algorithms in terms of just what they are: Ideas of how something is computed. Counting milliseconds won’t help us in that. It’s quite possible that a bad algorithm written in a low-level programming language such as assembly runs much quicker than a good algorithm written in a high-level programming language such as Python or Ruby. So it’s time to define what a “better algorithm” really is.

As algorithms are programs that perform just a computation, and not other things computers often do such as networking tasks or user input and output, complexity analysis allows us to measure how fast a program is when it performs computations. Examples of operations that are purely computational include:

• numerical floating-point operations such as addition and multiplication

• searching within a database that fits in RAM for a given value

• running a regular expression pattern match on a string.

Clearly, computation is ubiquitous in computer programs. Complexity analysis is also a tool that allows us to explain how an algorithm behaves as the input grows larger. If we feed it a different input, how will the algorithm behave? If our algorithm takes 1 second to run for an input of size 1000, how will it behave if I double the input size? Will it run just as fast, half as fast, or four times slower? In practical programming, this is important as it allows us to predict how our algorithm will behave when the input data becomes larger. For example, if we’ve made an algorithm for a web application that works well with 1000 users and measure its running time, using algorithm complexity analysis we can have a pretty good idea of what will happen once we get 2000 users instead. For algorithmic competitions, complexity analysis gives us insight about how long our code will run for the largest test cases that are used to test our program’s correctness. So if we’ve measured our program’s behaviour for a small input, we can get a good idea of how it will behave for larger inputs.

Algorithm In mathematics and computer science, an algorithm is a step-by-step procedure for calculations. Algorithms are used for calculation, data processing, and automated reasoning. An algorithm is an effective method expressed as a finite list of well-defined instructions for calculating a function.

How do we compare algorithms ?

(1) Compare execution times? Not good: times are specific to a particular computer

(2) Count the number of statements executed?

Not good: number of statements vary with the programming language as well as the style of the individual programmer.

We need to define a number of objective measures. Ideal Solution: Express running time as a function of the input size n (i.e., f(n)). Compare different functions corresponding to running times. To compare two algorithms with running times f(n) and g(n) given, we need a rough measure that characterizes how fast each function grows. Such an analysis is independent of machine time, programming style, etc.

Counting instructions The maximum element in an array can be looked up using a simple piece of code written in javascript. Given an input array A of size n:

var M = A[ 0 ];

for ( var i = 0; i < n; ++i ) {

if ( A[ i ] >= M ) {

M = A[ i ];

}

}

Now, the first thing we’ll do is count how many fundamental instructions this piece of code executes. As we analyse this piece of code, we want to break it up into simple instructions; things that can be executed by the CPU directly - or close to that. We’ll assume our processor can execute the following operations as one instruction each:

• Assigning a value to a variable

• Looking up the value of a particular element in an array

• Comparing two values

• Incrementing a value

• Basic arithmetic operations such as addition and multiplication

We’ll assume branching (the choice between if and else parts of code after the if condition has been evaluated) occurs instantly and won’t count these instructions. In the above code, the first line of code is: var M = A[ 0 ];

This requires 2 instructions: One for looking up A[ 0 ] and one for assigning the value to M (we’re assuming that n is always at least 1). These two instructions are always required by the algorithm, regardless of the value of n. The for loop initialization code also has to always run. This gives us two more instructions; an assignment and a comparison: i = 0; i < n;

These will run before the first for loop iteration. After each for loop iteration, we need two more instructions to run, an increment of i and a comparison to check if we’ll stay in the loop: ++i; i < n;

So, if we ignore the loop body, the number of instructions this algorithm needs is 4 + 2n. That is, 4 instructions at the beginning of the for loop and 2 instructions at the end of each iteration of which we have n. We can now define a mathematical function f( n ) that, given an n, gives us the number of instructions the algorithm needs. For an empty for body, we have f( n ) = 4 + 2n.

Kinds of Analysis

Worst-case maximum time of an algorithm on any input of size n The worst case analysis of an algorithm provides an upper bound on running time and an absolute guarantee that the algorithm would not run longer, no matter what the inputs are.

Average-case The expected time of algorithm over all inputs of size n. Need assumption of statistical distribution of inputs. The average case analysis provides the prediction about the running time and assumes that the input is random.

Best-case cheat with a slow algorithm that works fast on a particular input. The best case analysis of an algorithm provides a lower bound on running time. Input is the one for which the algorithm runs the fastest. Lower bound < running time < upper bound

Worst-case analysis Now, looking at the for body, we have an array lookup operation and a comparison that happen always: if ( A[ i ] >= M ) { … That’s two instructions right there. But the if body may run or may not run, depending on what the array values actually are. If it happens to be so that A[ i ] >= M, then we’ll run these two additional instructions — an array lookup and an assignment: M = A[ i ] But now we can’t define an f( n ) as easily, because our number of instructions doesn’t depend solely on n but also on our input. For example, for A = [ 1, 2, 3, 4 ] the algorithm will need more instructions than for A = [ 4, 3, 2, 1 ]. When analysing algorithms, we often consider the worst-case scenario. What’s the worst that can happen for our algorithm? When does our algorithm need the most instructions to complete? In this case, it is when we have an array in increasing order such as A = [ 1, 2, 3, 4 ]. In that case, M needs to be replaced every single time and so that yields the most instructions. Computer scientists have a fancy name for that and they call it worst-case analysis; that’s nothing more than just considering the case when we’re the most unlucky. So, in the worst case, we have 4 instructions to run within the for body, so we have f( n ) = 4 + 2n + 4n = 6n + 4. This function f, given a problem size n, gives us the number of instructions that would be needed in the worst-case.

Asymptotic behavior

In our function, 6n + 4, we have two terms: 6n and 4. In complexity analysis we only care about what happens to the instruction-counting function as the program input (n) grows large. This really goes along with the previous ideas of “worst-case scenario” behaviour: We’re interested in how our algorithm behaves when treated badly; when it’s challenged to do something hard. Notice that this is really useful when comparing algorithms. If an algorithm beats another algorithm for a large input, it’s most probably true that the faster algorithm remains faster when given an easier, smaller input. From the terms that we are considering, we’ll drop all the terms that grow slowly and only keep the ones that grow fast as n becomes larger. Clearly 4 remains a 4 as n grows larger, but 6n grows larger and larger, so it tends to matter more and more for larger problems. Therefore, the first thing we will do is drop the 4 and keep the function as f( n ) = 6n. This makes sense if you think about it, as the 4 is simply an “initialization constant”. Different programming languages may require a different time to set up. For example, Java needs some time to initialize its virtual machine. Since we’re ignoring programming language differences, it only makes sense to ignore this value. The second thing we’ll ignore is the constant multiplier in front of n, and so our function will become f( n ) = n. As you can see this simplifies things quite a lot. Again, it makes some sense to drop this multiplicative constant if we think about how different programming languages compile. The “array lookup” statement in one language may compile to different instructions in different programming languages. For example, in C, doing A[ i ] does not include a check that i is within the declared array size, while in Pascal it does. So, the following Pascal code: M := A[ i ] Is the equivalent of the following in C: if ( i >= 0 && i < n ) { M = A[ i ]; } So it’s reasonable to expect that different programming languages will yield different factors when we count their instructions. In our example in which we are using a dumb compiler for Pascal that is oblivious of possible optimizations, Pascal requires 3 instructions for each array access instead of the 1 instruction C requires. Dropping this factor goes along the lines of ignoring the differences between particular programming languages and compilers and only analysing the idea of the algorithm itself. This filter of “dropping all factors” and of “keeping the largest growing term” as described above is what we call asymptotic behaviour. So the asymptotic behaviour of f( n ) = 2n + 8 is described by the function f( n ) = n. Mathematically speaking, what we’re saying here is that we’re interested in the limit of function f as n tends to infinity. In a strict mathematical setting, we would not be able to drop the constants in the limit; but for computer science purposes, we want to do that for the reasons described above. Now let us find the asymptotic behaviour of the following example functions by dropping the constant factors and by keeping the terms that grow the fastest.

- f( n ) = 5n + 12 gives f( n ) = n. By using the exact same reasoning as above.

- f( n ) = 109 gives f( n ) = 1. We’re dropping the multiplier 109 * 1, but we still have to put a 1 here to indicate that this function has a non-zero value.

- f( n ) = n2 + 3n + 112 gives f( n ) = n2 Here, n2 grows larger than 3n for sufficiently large n, so we’re keeping that.

- f( n ) = n3 + 1999n + 1337 gives f( n ) = n3 Even though the factor in front of n is quite large, we can still find a large enough n so that n3 is bigger than 1999n. As we’re interested in the behaviour for very large values of n, we only keep n^3 Some more examples

- f( n ) = n6 + 3n

- f( n ) = 2n + 12

- f( n ) = 3n + 2n

- f( n ) = nn + n

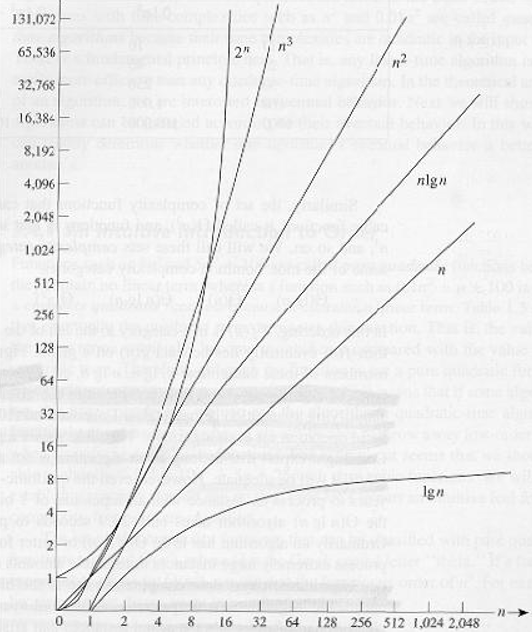

If you’re having trouble with one of the above, plug in some large n and see which term is bigger. Asymptotic curves of some common functions. Don’t forget to check the values of each function for large values of input x.

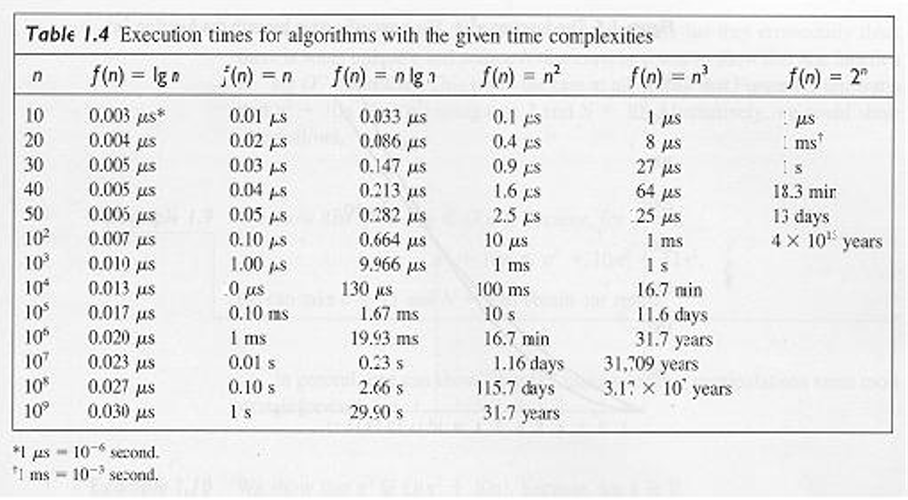

Execution time for common functions Complexity So what this is telling us is that since we can drop all these decorative constants, it’s pretty easy to tell the asymptotic behaviour of the instruction-counting function of a program. In fact, any program that doesn’t have any loops will have f( n ) = 1, since the number of instructions it needs is just a constant (unless it uses recursion; see below). Any program with a single loop which goes from 1 to n will have f( n ) = n, since it will do a constant number of instructions before the loop, a constant number of instructions after the loop, and a constant number of instructions within the loop which all run n times. This should now be much easier and less tedious than counting individual instructions, so let’s take a look at a couple of examples to get familiar with this. The following PHP program checks to see if a particular value exists within an array A of size n:

<?php

$exists = false;

for ( $i = 0; $i < n; ++$i ) {

if ( $A[ $i ] == $value ) {

$exists = true;

break;

This method of searching for a value within an array is called linear search. This is a reasonable name, as this program has f( n ) = n . You may notice that there’s a “break” statement here that may make the program terminate sooner, even after a single iteration. But recall that we’re interested in the worst-case scenario, which for this program is for the array A to not contain the value. So we still have f( n ) = n.

Systematically analyse the number of instructions the above PHP program needs with respect to n in the worst-case to find f( n ), similarly to how we analysed our first Javascript program. Then verify that, asymptotically, we have f( n ) = n.

Let’s look at a Python program which adds two array elements together to produce a sum which it stores in another variable: v = a[ 0 ] + a[ 1 ] Here we have a constant number of instructions, so we have f( n ) = 1. The following program in C++ checks to see if a vector (a form of array) named A of size n contains the same two values anywhere within it: bool duplicate = false; for ( int i = 0; i < n; ++i ) { for ( int j = 0; j < n; ++j ) { if ( i != j && A[ i ] == A[ j ] ) { duplicate = true; break; } } if ( duplicate ) { break; } }

As here we have two nested loops within each other, we’ll have an asymptotic behaviour described by f( n ) = n^2(n-square).

Note: Simple programs can be analysed by counting the nested loops of the program. A single loop over n items yields f( n ) = n. A loop within a loop yields f( n ) = n2. A loop within a loop within a loop yields f( n ) = n3. If we have a program that calls a function within a loop and we know the number of instructions the called function performs, it’s easy to determine the number of instructions of the whole program. Indeed, let’s take a look at this C example: int i; for ( i = 0; i < n; ++i ) { f( n ); } If we know that f( n ) is a function that performs exactly n instructions, we can then know that the number of instructions of the whole program is asymptotically n2, as the function is called exactly n times.

note: Given a series of for loops that are sequential, the slowest of them determines the asymptotic behaviour of the program. Two nested loops followed by a single loop is asymptotically the same as the nested loops alone, because the nested loops dominate the simple loop.

Now, let’s switch over to the fancy notation that computer scientists use. When we’ve figured out the exact such f asymptotically, we’ll say that our program is Θ( f( n ) ). For example, the above programs are Θ( 1 ), Θ( n2 ) and Θ( n2 ) respectively. Θ( n ) is pronounced “theta of n”. Sometimes we say that f( n ), the original function counting the instructions including the constants, is Θ( something ). For example, we may say that f( n ) = 2n is a function that is Θ( n ) — nothing new here. We can also write 2n ∈ Θ( n ), which is pronounced as “two n is theta of n”. Don’t get confused about this notation: All it’s saying is that if we’ve counted the number of instructions a program needs and those are 2n, then the asymptotic behaviour of our algorithm is described by n, which we found by dropping the constants. Given this notation, the following are some true mathematical statements:

- n6 + 3n ∈ Θ( n6 )

- 2n + 12 ∈ Θ( 2n )

- 3n + 2n ∈ Θ( 3n )

- nn + n ∈ Θ( nn )

We call this function, i.e. what we put within Θ( here ), the time complexity or just complexity of our algorithm. So an algorithm with Θ( n ) is of complexity n. We also have special names for Θ( 1 ), Θ( n ), Θ( n2 ) and Θ( log( n ) ) because they occur very often. We say that a Θ( 1 ) algorithm is a constant-time algorithm, Θ( n ) is linear, Θ( n2 ) is quadratic and Θ( log( n ) ) is logarithmic.

note: Programs with a bigger Θ run slower than programs with a smaller Θ.

Time/Space trade off A programmer usually has a choice of data structures and algorithms to use. Choosing the best one for a particular job involves, among other factors, two important measures: Time Complexity: how much time will the program take? Space Complexity: how much storage will the program need? A programmer will sometimes seek a trade-off between space and time complexity. For example, a programmer might choose a data structure that requires a lot of storage in order to reduce the computation time. There is an element of art in making such trade-offs, but the programmer must make the choice from an informed point of view. The programmer must have some verifiable basis on which to make the selection of a data structure or algorithm. Complexity analysis provides such a basis. Complexity refers to the rate at which the storage or time grows as a function of the problem size. The absolute growth depends on the machine used to execute the program, the compiler used to construct the program, and many other factors. We would like to have a way of describing the inherent complexity of a program (or piece of a program), independent of machine/compiler considerations. This means that we must not try to describe the absolute time or storage needed. We must instead concentrate on a “proportionality” approach, expressing the complexity in terms of its relationship to some known function. This type of analysis is known as asymptotic analysis. Asymptotic analysis is based on the idea that as the problem size grows, the complexity can be described as a simple proportionality to some known function. This idea is incorporated in the “Big Oh” notation for asymptotic performance.

Definition: T(n) = O(f(n)) if and only if there are constants c0 and n0 such that T(n) <= c0 f(n) for all n >= n0. The expression “T(n) = O(f(n))” is read as “T of n is in Big Oh of f of n.” Big Oh is sometimes said to describe an “upper-bound” on the complexity. Other forms of asymptotic analysis (“Big Omega”, “Little Oh”, “Theta”) are similar in spirit to Big Oh.

Big-O notation Now, it’s sometimes true that it will be hard to figure out exactly the behaviour of an algorithm in this fashion as we did above, especially for more complex examples. However, we will be able to say that the behaviour of our algorithm will never exceed a certain bound. This will make life easier for us, as we won’t have to specify exactly how fast our algorithm runs, even when ignoring constants the way we did before. All we’ll have to do is find a certain bound. This is explained easily with an example. A famous problem computer scientists use for teaching algorithms is the sorting problem. In the sorting problem, an array A of size n is given and we are asked to write a program that sorts this array. This problem is interesting because it is a pragmatic problem in real systems. For example, a file explorer needs to sort the files it displays by name so that the user can navigate them with ease. Sorting is also interesting because there are many algorithms to solve it, some of which are worse than others. It’s also an easy problem to define and to explain. So let’s write a piece of code that sorts an array. Here is an inefficient way to implement sorting an array in Ruby. (Of course, Ruby supports sorting arrays using build-in functions which you should use instead, and which are certainly faster than what we’ll see here. But this is here for illustration purposes.) b = [] n.times do m = a[ 0 ] mi = 0 a.each_with_index do |element, i| if element < m m = element mi = i end end a.delete_at( mi ) b « m end

This method is called selection sort. It finds the minimum of our array (the array is denoted a above, while the minimum value is denoted m and mi is its index), puts it at the end of a new array (in our case b), and removes it from the original array. Then it finds the minimum between the remaining values of our original array, appends that to our new array so that it now contains two elements, and removes it from our original array. It continues this process until all items have been removed from the original and have been inserted into the new array, which means that the array has been sorted. In this example, we can see that we have two nested loops. The outer loop runs n times, and the inner loop runs once for each element of the array a. While the array a initially has n items, we remove one array item in each iteration. So the inner loop repeats n times during the first iteration of the outer loop, then n - 1 times, then n - 2 times and so forth, until the last iteration of the outer loop during which it only runs once. It’s a little harder to evaluate the complexity of this program, as we’d have to figure out the sum 1 + 2 + … + (n - 1) + n. But we can for sure find an “upper bound” for it. That is, we can alter our program to make it worse than it is and then find the complexity of that new program that we derived. If we can find the complexity of the worse program that we’ve constructed, then we know that our original program is at most that bad, or maybe better. That way, if we find out a pretty good complexity for our altered program, which is worse than our original, we can know that our original program will have a pretty good complexity too – either as good as our altered program or even better. Let’s now think of the way to edit this example program to make it easier to figure out its complexity. But let’s keep in mind that we can only make it worse, i.e. make it take up more instructions, so that our estimate is meaningful for our original program. Clearly we can alter the inner loop of the program to always repeat exactly n times instead of a varying number of times. Some of these repetitions will be useless, but it will help us analyse the complexity of the resulting algorithm. If we make this simple change, then the new algorithm that we’ve constructed is clearly Θ( n2 ), because we have two nested loops where each repeats exactly n times. If that is so, we say that the original algorithm is O( n2 ). O( n2 ) is pronounced “big oh of n squared”. What this says is that our program is asymptotically no worse than n2. It may even be better than that, or it may be the same as that. By the way, if our program is indeed Θ( n2 ), we can still say that it’s O( n2 ). To help you realize that, imagine altering the original program in a way that doesn’t change it much, but still makes it a little worse, such as adding a meaningless instruction at the beginning of the program. Doing this will alter the instruction-counting function by a simple constant, which is ignored when it comes to asymptotic behaviour. So a program that is Θ( n2 ) is also O( n2 ). But a program that is O( n2 ) may not be Θ( n2 ). For example, any program that is Θ( n ) is also O( n2 ) in addition to being O( n ). If we imagine the that a Θ( n ) program is a simple for loop that repeats n times, we can make it worse by wrapping it in another for loop which repeats n times as well, thus producing a program with f( n ) = n2. To generalize this, any program that is Θ( a ) is O( b ) when b is worse than a. Notice that our alteration to the program doesn’t need to give us a program that is actually meaningful or equivalent to our original program. It only needs to perform more instructions than the original for a given n. All we’re using it for is counting instructions, not actually solving our problem. So, saying that our program is O( n2 ) is being on the safe side: We’ve analysed our algorithm, and we’ve found that it’s never worse than n2. But it could be that it’s in fact n2. This gives us a good estimate of how fast our program runs. Let’s go through a few examples to help you familiarize yourself with this new notation.

Find out which of the following are true:

- A Θ( n ) algorithm is O( n )

- A Θ( n ) algorithm is O( n2 )

- A Θ( n2 ) algorithm is O( n3 )

- A Θ( n ) algorithm is O( 1 )

- A O( 1 ) algorithm is Θ( 1 )

- A O( n ) algorithm is Θ( 1 ) Solutions

- We know that this is true as our original program was Θ( n ). We can achieve O( n ) without altering our program at all.

- As n2 is worse than n, this is true.

- As n3 is worse than n2, this is true.

- As 1 is not worse than n, this is false. If a program takes n instructions asymptotically (a linear number of instructions), we can’t make it worse and have it take only 1 instruction asymptotically (a constant number of instructions).

- This is true as the two complexities are the same.

- This may or may not be true depending on the algorithm. In the general case it’s false. If an algorithm is Θ( 1 ), then it certainly is O( n ). But if it’s O( n ) then it may not be Θ( 1 ). For example, a Θ( n ) algorithm is O( n ) but not Θ( 1 ).

Use an arithmetic progression sum to prove that the above program is not only O( n2 ) but also Θ( n2 ). Because the O-complexity of an algorithm gives an upper bound for the actual complexity of an algorithm, while Θ gives the actual complexity of an algorithm, we sometimes say that the Θ gives us a tight bound. If we know that we’ve found a complexity bound that is not tight, we can also use a lower-case o to denote that. For example, if an algorithm is Θ( n ), then its tight complexity is n. Then this algorithm is both O( n ) and O( n2 ). As the algorithm is Θ( n ), the O( n ) bound is a tight one. But the O( n2 ) bound is not tight, and so we can write that the algorithm is o( n2 ), which is pronounced “small o of n squared” to illustrate that we know our bound is not tight. It’s better if we can find tight bounds for our algorithms, as these give us more information about how our algorithm behaves, but it’s not always easy to do.

Determine which of the following bounds are tight bounds and which are not tight bounds. Check to see if any bounds may be wrong. Use o( notation ) to illustrate the bounds that are not tight.

- A Θ( n ) algorithm for which we found a O( n ) upper bound.

- A Θ( n2 ) algorithm for which we found a O( n3 ) upper bound.

- A Θ( 1 ) algorithm for which we found an O( n ) upper bound.

- A Θ( n ) algorithm for which we found an O( 1 ) upper bound.

- A Θ( n ) algorithm for which we found an O( 2n ) upper bound. Solution

- In this case, the Θ complexity and the O complexity are the same, so the bound is tight.

- Here we see that the O complexity is of a larger scale than the Θ complexity so this bound is not tight. Indeed, a bound of O( n2 ) would be a tight one. So we can write that the algorithm is o( n3 ).

- Again we see that the O complexity is of a larger scale than the Θ complexity so we have a bound that isn’t tight. A bound of O( 1 ) would be a tight one. So we can point out that the O( n ) bound is not tight by writing it as o( n ).

- We must have made a mistake in calculating this bound, as it’s wrong. It’s impossible for a Θ( n ) algorithm to have an upper bound of O( 1 ), as n is a larger complexity than 1. Remember that O gives an upper bound.

- This may seem like a bound that is not tight, but this is not actually true. This bound is in fact tight. Recall that the asymptotic behavior of 2n and n are the same, and that O and Θ are only concerned with asymptotic behavior. So we have that O( 2n ) = O( n ) and therefore this bound is tight as the complexity is the same as the Θ.

note: It’s easier to figure out the O-complexity of an algorithm than its Θ-complexity. In the example above, we modified our program to make it worse (i.e. taking more instructions and therefore more time) and created the O notation. O is meaningful because it tells us that our program will never be slower than a specific bound, and so it provides valuable information so that we can argue that our program is good enough. If we do the opposite and modify our program to make it better and find out the complexity of the resulting program, we use the notation Ω. Ω therefore gives us a complexity that we know our program won’t be better than. This is useful if we want to prove that a program runs slowly or an algorithm is a bad one. This can be useful to argue that an algorithm is too slow to use in a particular case. For example, saying that an algorithm is Ω( n3 ) means that the algorithm isn’t better than n3. It might be Θ( n3 ), as bad as Θ( n4 ) or even worse, but we know it’s at least somewhat bad. So Ω gives us a lower bound for the complexity of our algorithm. Similarly to ο, we can write ω if we know that our bound isn’t tight. For example, a Θ( n3 ) algorithm is ο( n4 ) and ω( n2 ). Ω( n ) is pronounced “big omega of n”, while ω( n ) is pronounced “small omega of n”.

For the following Θ complexities write down a tight and a non-tight O bound, and a tight and non-tight Ω bound of your choice, providing they exist.

- Θ( 1 )

- Θ( n )

- Θ( n2 )

- Θ( n3 ) Solution This is a straight-forward application of the definitions above.

- The tight bounds will be O( 1 ) and Ω( 1 ). A non-tight O-bound would be O( n ). Recall that O gives us an upper bound. As n is of larger scale than 1 this is a non-tight bound and we can write it as o( n ) as well. But we cannot find a non-tight bound for Ω, as we can’t get lower than 1 for these functions. So we’ll have to do with the tight bound.

- The tight bounds will have to be the same as the Θ complexity, so they are O( n ) and Ω( n ) respectively. For non-tight bounds we can have O( n ), as n is larger than 1 and so it is an upper bound for n. As we know this is a non-tight upper bound, we can also write it as o( n ). For a lower bound that is not tight, we can simply use Ω( 1 ). As we know that this bound is not tight, we can also write it as ω( 1 ).

- The tight bounds are O( n ) and Ω( n ). Two non-tight bounds could be ω( 1 ) and o( n3 ). These are in fact pretty bad bounds, as they are far from the original complexities, but they are still valid using our definitions.

- The tight bounds are O( n2 ) and Ω( n2 ). For non-tight bounds we could again use ω( 1 ) and o( n3 ) as in our previous example.

- The tight bounds are O( n3 ) and Ω( n3 ) respectively. Two non-tight bounds could be ω( n2 ) and o( n3 ). Although these bounds are not tight, they’re better than the ones we gave above.

The reason we use O and Ω instead of Θ even though O and Ω can also give tight bounds is that we may not be able to tell if a bound we’ve found is tight, or we may just not want to go through the process of scrutinizing it so much. Among all of those symbols the most important symbols are O and Θ. Also note that although Ω gives us a lower-bound behavior for our function (i.e. we’ve improved our program and made it perform less instructions) we’re still referring to a “worst-case” analysis. This is because we’re feeding our program the worst possible input for a given n and analyzing its behavior under this assumption. The following table indicates the symbols we just introduced and their correspondence with the usual mathematical symbols of comparisons that we use for numbers. The reason we don’t use the usual symbols here and use Greek letters instead is to point out that we’re doing an asymptotic behavior comparison, not just a simple comparison.

Asymptotic comparison operator Numeric comparison operator Our algorithm is o( something ) A number is < something Our algorithm is O( something ) A number is ≤ something Our algorithm is Θ( something ) A number is = something Our algorithm is Ω( something ) A number is ≥ something Our algorithm is ω( something ) A number is > something

note: While all the symbols O, o, Ω, ω and Θ are useful at times, O(big-oh) is the one used more commonly, as it’s easier to determine than Θ and more practically useful than Ω.

If a function T(n) = O(f(n)), then eventually the value cf(n) will exceed the value of T(n) for some constant c. “Eventually” means “after n exceeds some value.” Does this really mean anything useful? We might say (correctly) that n2 + 2n = O(n25), but we don’t get a lot of information from that; n25 is simply too big. When we use Big Oh analysis, we usually choose the function f(n) to be as small as possible and still satisfy the definition of Big Oh. Thus, it is more meaningful to say that n2 + 2n = O(n2); this tells us something about the growth pattern of the function n2 + 2n, namely that the n2 term will dominate the growth as n increases. The following functions are often encountered in computer science Big Oh analysis: • T(n) = O(1). This is called constant growth. T(n) does not grow at all as a function of n, it is a constant. It is pronounced “Big Oh of one.” For example, array access has this characteristic. A[i] takes the same time independent of the size of the array A. • T(n) = O(lg(n)). This is called logarithmic growth. T(n) grows proportional to the base 2 logarithm of n. Actually, the base doesn’t matter, it’s just traditional to use base-2 in computer science. It is pronounced “Big Oh of log n.” For example, binary search has this characteristic. • T(n) = O(n). This is called linear growth. T(n) grows linearly with n. It is pronounced “Big Oh of n.” For example, looping over all the elements in a one-dimensional array would be an O(n) operation. • T(n) = O(n log n). This is called “n log n” growth. T(n) grows proportional to n times the base 2 logarithm of n. It is pronounced “Big Oh of n log n.” For example, Merge Sort has this characteristic. In fact, no sorting algorithm that uses comparison between elements can be faster than n log n. • T(n) = O(nk). This is called polynomial growth. T(n) grows proportional to the k-th power of n. We rarely consider algorithms that run in time O(nk) where k is greater than 5, because such algorithms are very slow. For example, selection sort is an O(n2) algorithm. It is pronounced “Big Oh of n squared.” • T(n) = O(2n) This is called exponential growth. T(n) grows exponentially. It is pronounced “Big Oh of 2 to the n.” Exponential growth is the most-feared growth pattern in computer science; algorithms that grow this way are basically useless for anything but very small problems. The growth patterns above have been listed in order of increasing “size.” That is, O(1), O(lg(n)), O(n lg(n)), O(n2), O(n3), … , O(2n). Note that it is not true that if f(n) = O(g(n)) then g(n) = O(f(n)). The “=” sign does not mean equality in the usual algebraic sense — that’s why some people say “f(n) is in Big Oh of g(n)” and we never say “f(n)equals Big Oh of g(n).”

Big Oh Does Not Tell the Whole Story Suppose you have a choice of two approaches to writing a program. Both approaches have the same asymptotic performance (for example, both are O(n lg(n)). Why select one over the other, they’re both the same, right? They may not be the same. There is this small matter of the constant of proportionality. Suppose algorithms A and B have the same asymptotic performance, TA(n) = TB(n) = O(g(n)). Now suppose that A does ten operations for each data item, but algorithm B only does three. It is reasonable to expect B to be faster than A even though both have the same asymptotic performance. The reason is that asymptotic analysis ignores constants of proportionality. As a specific example, let’s say that algorithm A is { set up the algorithm, taking 50 time units; read in n elements into array A; /* 3 units per element / for (i = 0; i < n; i++) { do operation1 on A[i]; / takes 10 units / do operation2 on A[i]; / takes 5 units / do operation3 on A[i]; / takes 15 units */ } } Let’s now say that algorithm B is

{ set up the algorithm, taking 200 time units; read in n elements into array A; /* 3 units per element / for (i = 0; i < n; i++) { do operation1 on A[i]; / takes 10 units / do operation2 on A[i]; / takes 5 units / } } Algorithm A sets up faster than B, but does more operations on the data. The execution time of A and B will be TA(n) = 50 + 3n + (10 + 5 + 15)n = 50 + 33n and TB(n) =200 + 3n + (10 + 5)n = 200 + 18*n respectively. Algorithm A is the better choice for small values of n. For values of n > 10, algorithm B is the better choice. Remember that both algorithms have time complexity O(n).

Logarithms A logarithm is an operation applied to a number that makes it quite smaller – much like a square root of a number. So if there’s one thing you want to remember about logarithms is that they take a number and make it much smaller than the original. Now, in the same way that square roots are the inverse operation of squaring something, logarithms are the inverse operation of exponentiating something. Consider the equation: 2x = 1024 We now wish to solve this equation for x. So we ask ourselves: What is the number to which we must raise the base 2 so that we get 1024? That number is 10. Indeed, we have 2^10 = 1024, which is easy to verify. Logarithms help us denote this problem using new notation. In this case, 10 is the logarithm of 1024 and we write this as log( 1024 ) and we read it as “the logarithm of 1024”. Because we’re using 2 as a base, these logarithms are called base 2 logarithms. There are logarithms in other bases, but we’ll only use base 2 logarithms in this article. In computer science, base 2 logarithms are much more common than any other types of logarithms. This is because we often only have two different entities: 0 and 1. We also tend to cut down one big problem into halves, of which there are always two. So you only need to know about base-2 logarithms to continue with this article.

Solve the equations below. Denote what logarithm you’re finding in each case. Use only logarithms base 2.

- 2x = 64

- (22)x = 64

- 4x = 4

- 2x = 1

- 2x + 2x = 32

- (2x) * (2x) = 64 Solution There is nothing more to this than applying the ideas defined above.

- By trial and error we can find that x = 6 and so log( 64 ) = 6.

- Here we notice that (22)x, by the properties of exponents, can be written as 22x. So we have that 2x = 6 because log( 64 ) = 6 from the previous result and therefore x = 3.

- Using our knowledge from the previous equation, we can write 4 as 22 and so our equation becomes (22)x = 4 which is the same as 22x = 4. Then we notice that log( 4 ) = 2 because 22 = 4 and therefore we have that 2x = 2. So x = 1. This is readily observed from the original equation, as using an exponent of 1 yields the base as a result.

- Recall that an exponent of 0 yields a result of 1. So we have log( 1 ) = 0 as 20 = 1, and so x = 0.

- Here we have a sum and so we can’t take the logarithm directly. However we notice that 2x + 2x is the same as 2 * (2x). So we’ve multiplied in yet another two, and therefore this is the same as 2x + 1 and now all we have to do is solve the equation 2x + 1 = 32. We find that log( 32 ) = 5 and so x + 1 = 5 and therefore x = 4.

- We’re multiplying together two powers of 2, and so we can join them by noticing that (2x) * (2x) is the same as 22x. Then all we need to do is to solve the equation 22x = 64 which we already solved above and so x = 3.

note: For competition algorithms implemented in C++, once you’ve analyzed your complexity, you can get a rough estimate of how fast your program will run by expecting it to perform about 1,000,000 operations per second, where the operations you count are given by the asymptotic behavior function describing your algorithm. For example, a Θ( n ) algorithm takes about a second to process the input for n = 1,000,000.

Recursive complexity Let’s now take a look at a recursive function. A recursive function is a function that calls itself. Can we analyze its complexity? The following function, written in Python, evaluates the factorial of a given number. def factorial( n ): if n == 1: return 1 return n * factorial( n - 1 )

Let us analyze the complexity of this function. This function doesn’t have any loops in it, but its complexity isn’t constant either. What we need to do to find out its complexity is again to go about counting instructions. Clearly, if we pass some n to this function, it will execute itself n times. If you’re unsure about that, run it “by hand” now for n = 5 to validate that it actually works. For example, for n = 5, it will execute 5 times, as it will keep decreasing n by 1 in each call. We can see therefore that this function is then Θ( n ). If you’re unsure about this fact, remember that you can always find the exact complexity by counting instructions. If you wish, you can now try to count the actual instructions performed by this function to find a function f( n ) and see that it’s indeed linear (recall that linear means Θ( n ).

Logarithmic complexity One famous problem in computer science is that of searching for a value within an array. We solved this problem earlier for the general case. This problem becomes interesting if we have an array which is sorted and we want to find a given value within it. One method to do that is called binary search. We look at the middle element of our array: If we find it there, we’re done. Otherwise, if the value we find there is bigger than the value we’re looking for, we know that our element will be on the left part of the array. Otherwise, we know it’ll be on the right part of the array. We can keep cutting these smaller arrays in halves until we have a single element to look at. Here’s the method using pseudocode: def binarySearch( A, n, value ): if n = 1: if A[ 0 ] = value: return true else: return false if value < A[ n / 2 ]: return binarySearch( A[ 0…( n / 2 - 1 ) ], n / 2 - 1, value ) else if value > A[ n / 2 ]: return binarySearch( A[ ( n / 2 + 1 )…n ], n / 2 - 1, value ) else: return true

This pseudocode is a simplification of the actual implementation. In practice, this method is easier described than implemented, as the programmer needs to take care of some implementation issues. There are off-by-one errors and the division by 2 may not always produce an integer value and so it’s necessary to floor() or ceil() the value. But we can assume for our purposes that it will always succeed, and we’ll assume our actual implementation in fact takes care of the off-by-one errors, as we only want to analyze the complexity of this method. Let us now attempt to analyze this algorithm. Again, we have a recursive algorithm in this case. Let’s assume, for simplicity, that the array is always cut in exactly a half, ignoring just now the + 1 and - 1 part in the recursive call. By now you should be convinced that a little change such as ignoring + 1 and - 1 won’t affect our complexity results. This is a fact that we would normally have to prove if we wanted to be prudent from a mathematical point of view, but practically it is intuitively obvious. Let’s assume that our array has a size that is an exact power of 2, for simplicity. Again this assumption doesn’t change the final results of our complexity that we will arrive at. The worst-case scenario for this problem would happen when the value we’re looking for does not occur in our array at all. In that case, we’d start with an array of size n in the first call of the recursion, then get an array of size n / 2 in the next call. Then we’ll get an array of size n / 4 in the next recursive call, followed by an array of size n / 8 and so forth. In general, our array is split in half in every call, until we reach 1. So, let’s write the number of elements in our array for every call:

- 0th iteration: n

- 1st iteration: n / 2

- 2nd iteration: n / 4

- 3rd iteration: n / 8

- …

- ith iteration: n / 2i

- …

- last iteration: 1

Notice that in the i-th iteration, our array has n / 2i elements. This is because in every iteration we’re cutting our array into half, meaning we’re dividing its number of elements by two. This translates to multiplying the denominator with a 2. If we do that i times, we get n / 2i. Now, this procedure continues and with every larger i we get a smaller number of elements until we reach the last iteration in which we have only 1 element left. If we wish to find i to see in what iteration this will take place, we have to solve the following equation: 1 = n / 2i This will only be true when we have reached the final call to the binarySearch() function, not in the general case. So solving for i here will help us find in which iteration the recursion will finish. Multiplying both sides by 2i we get: 2i = n Solving for i we have: i = log( n ) This tells us that the number of iterations required to perform a binary search is log( n ) where n is the number of elements in the original array. If you think about it, this makes some sense. For example, take n = 32, an array of 32 elements. How many times do we have to cut this in half to get only 1 element? We get: 32 → 16 → 8 → 4 → 2 → 1. We did this 5 times, which is the logarithm of 32. Therefore, the complexity of binary search is Θ( log( n ) ). This last result allows us to compare binary search with linear search, our previous method. Clearly, as log( n ) is much smaller than n, it is reasonable to conclude that binary search is a much faster method to search within an array then linear search, so it may be advisable to keep our arrays sorted if we want to do many searches within them.

note: Improving the asymptotic running time of a program often tremendously increases its performance, much more than any smaller “technical” optimizations such as using a faster programming language.

Optimal sorting You now know about analyzing the complexity of algorithms, asymptotic behavior of functions and big-O notation. You also know how to intuitively figure out that the complexity of an algorithm is O( 1 ), O( log( n ) ), O( n ), O( n2 ) and so forth. You know the symbols o, O, ω, Ω and Θ and what worst-case analysis means.

We looked at a sorting implementation above called a selection sort. We mentioned that selection sort is not optimal. An optimal algorithm is an algorithm that solves a problem in the best possible way, meaning there are no better algorithms for this. This means that all other algorithms for solving the problem have a worse or equal complexity to that optimal algorithm. There may be many optimal algorithms for a problem that all share the same complexity. The sorting problem can be solved optimally in various ways. We can use the same idea as with binary search to sort quickly. This sorting method is called mergesort. To perform a merge sort, we will first need to build a helper function that we will then use to do the actual sorting. We will make a merge function which takes two arrays that are both already sorted and merges them together into a big sorted array. This is easily done: def merge( A, B ): if empty( A ): return B if empty( B ): return A if A[ 0 ] < B[ 0 ]: return concat( A[ 0 ], merge( A[ 1…A_n ], B ) ) else: return concat( B[ 0 ], merge( A, B[ 1…B_n ] ) )

The concat function takes an item, the “head”, and an array, the “tail”, and builds up and returns a new array which contains the given “head” item as the first thing in the new array and the given “tail” item as the rest of the elements in the array. For example, concat( 3, [ 4, 5, 6 ] ) returns [ 3, 4, 5, 6 ]. We use A_n and B_n to denote the sizes of arrays A and B respectively.

Verify that the above function actually performs a merge. Rewrite it in your favourite programming language in an iterative way (using for loops) instead of using recursion. Analyzing this algorithm reveals that it has a running time of Θ( n ), where n is the length of the resulting array (n = A_n + B_n).

Verify that the running time of merge is Θ( n ). Utilizing this function we can build a better sorting algorithm. The idea is the following: We split the array into two parts. We sort each of the two parts recursively, then we merge the two sorted arrays into one big array. In pseudocode: def mergeSort( A, n ): if n = 1: return A # it is already sorted middle = floor( n / 2 ) leftHalf = A[ 1…middle ] rightHalf = A[ ( middle + 1 )…n ] return merge( mergeSort( leftHalf, middle ), mergeSort( rightHalf, n - middle ) )

Verify the correctness of mergeSort. That is, check to see if mergeSort as defined above actually correctly sorts the array it is given. If you’re having trouble understanding why it works, try it with a small example array and run it “by hand”. When running this function by hand, make sure leftHalf and rightHalf are what you get if you cut the array approximately in the middle; it doesn’t have to be exactly in the middle if the array has an odd number of elements (that’s what floor above is used for). As a final example, let us analyze the complexity of mergeSort. In every step of mergeSort, we’re splitting the array into two halves of equal size, similarly to binarySearch. However, in this case, we maintain both halves throughout execution. We then apply the algorithm recursively in each half. After the recursion returns, we apply the merge operation on the result which takes Θ( n ) time. So, we split the original array into two arrays of size n / 2 each. Then we merge those arrays, an operation that merges n elements and thus takes Θ( n ) time.

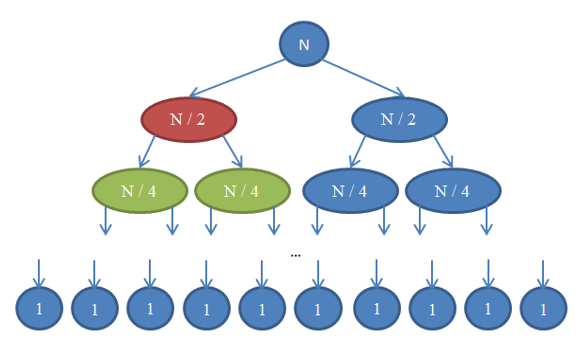

Let’s see what’s going on here. Each circle represents a call to the mergeSort function. The number written in the circle indicates the size of the array that is being sorted. The top blue circle is the original call to mergeSort, where we get to sort an array of size n. The arrows indicate recursive calls made between functions. The original call to mergeSort makes two calls to mergeSort on two arrays, each of size n / 2. This is indicated by the two arrows at the top. In turn, each of these calls makes two calls of its own to mergeSort two arrays of size n / 4 each, and so forth until we arrive at arrays of size 1. This diagram is called a recursion tree, because it illustrates how the recursion behaves and looks like a tree (the root is at the top and the leaves are at the bottom, so in reality it looks like an inversed tree). Notice that at each row in the above diagram, the total number of elements is n. To see this, take a look at each row individually. The first row contains only one call to mergeSort with an array of size n, so the total number of elements is n. The second row has two calls to mergeSort each of size n / 2. But n / 2 + n / 2 = n and so again in this row the total number of elements is n. In the third row, we have 4 calls each of which is applied on an n / 4-sized array, yielding a total number of elements equal to n / 4 + n / 4 + n / 4 + n / 4 = 4n / 4 = n. So again we getn elements. Now notice that at each row in this diagram the caller will have to perform a merge operation on the elements returned by the callees. For example, the circle indicated with red color has to sort n / 2 elements. To do this, it splits the n / 2-sized array into two n / 4-sized arrays, calls mergeSort recursively to sort those (these calls are the circles indicated with green color), then merges them together. This merge operation requires to merge n / 2 elements. At each row in our tree, the total number of elements merged is n. In the row that we just explored, our function merges n / 2 elements and the function on its right (which is in blue color) also has to merge n / 2 elements of its own. That yields n elements in total that need to be merged for the row we’re looking at. By this argument, the complexity for each row is Θ( n ). We know that the number of rows in this diagram, also called the depth of the recursion tree, will be log( n ). The reasoning for this is exactly the same as the one we used when analyzing the complexity of binary search. We have log( n ) rows and each of them is Θ( n ), therefore the complexity of mergeSort is Θ( n * log( n ) ). This is much better than Θ( n2 ) which is what selection sort gave us (remember that log( n ) is much smaller than n, and so n * log( n ) is much smaller than n * n = n2). If this sounds complicated to you, don’t worry: It’s not easy the first time you see it. Revisit this section and reread about the arguments here after you implement mergesort in your favourite programming language and validate that it works. As you saw in this last example, complexity analysis allows us to compare algorithms to see which one is better. Under these circumstances, we can now be pretty certain that merge sort will outperform selection sort for large arrays. This conclusion would be hard to draw if we didn’t have the theoretical background of algorithm analysis that we developed. In practice, indeed sorting algorithms of running time Θ( n * log( n ) ) are used. For example, the Linux kernel uses a sorting algorithm called heapsort, which has the same running time as mergesort which we explored here, namely Θ( n log( n ) ) and so is optimal. Notice that we have not proven that these sorting algorithms are optimal. Doing this requires a slightly more involved mathematical argument, but rest assured that they can’t get any better from a complexity point of view.

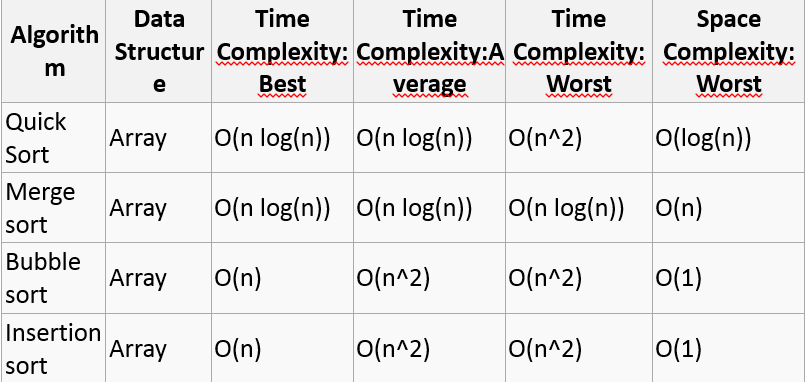

Searching/Sorting Algorithms, their asymptotic behavior and complexity analysis

Linear search on a list of n elements. In the worst case, the search must visit every element once. This happens when the value being searched for is either the last element in the list, or is not in the list. However, on average, assuming the value searched for is in the list and each list element is equally likely to be the value searched for, the search visits only n/2 elements. Insertion sort applied to a list of n elements, assumed to be all different and initially in random order. On average, half the elements in a list A1 … Aj are less than element Aj+1, and half are greater. Therefore the algorithm compares the j+1-st element to be inserted on the average with half the already sorted sub-list, so tj = j/2. Working out the resulting average-case running time yields a quadratic function of the input size, just like the worst-case running time. Quicksort applied to a list of n elements, again assumed to be all different and initially in random order. This popular sorting algorithm has an average-case performance of O(n log n), which contributes to making it a very fast algorithm in practice. But given a worst-case input, its performance degrades to O(n2).

Summary of the article Algorithmic complexity is concerned about how fast or slow particular algorithm performs. We define complexity as a numerical function T(n) - time versus the input size n. We want to define time taken by an algorithm without depending on the implementation details. But you agree that T(n) does depend on the implementation. A given algorithm will take different amounts of time on the same inputs depending on such factors as: processor speed; instruction set, disk speed, brand of compiler and etc. The way around is to estimate efficiency of each algorithm asymptotically. We will measure time T(n) as the number of elementary “steps” (defined in any way), provided each such step takes constant time.

Runtime Analysis One of the most important aspects of an algorithm is how fast it is. It is often easy to come up with an algorithm to solve a problem, but if the algorithm is too slow, it’s back to the drawing board. Since the exact speed of an algorithm depends on where the algorithm is run, as well as the exact details of its implementation, computer scientists typically talk about the runtime relative to the size of the input. For example, if the input consists of N integers, an algorithm might have a runtime proportional to N2, represented as O(N2). This means that if you were to run an implementation of the algorithm on your computer with an input of size N, it would take C*N2 seconds, where C is some constant that doesn’t change with the size of the input.

However, the execution time of many complex algorithms can vary due to factors other than the size of the input. For example, a sorting algorithm may run much faster when given a set of integers that are already sorted than it would when given the same set of integers in a random order. As a result, you often hear people talk about the worst-case runtime, or the average-case runtime. The worst-case runtime is how long it would take for the algorithm to run if it were given the most insidious of all possible inputs. The average-case runtime is the average of how long it would take the algorithm to run if it were given all possible inputs. Of the two, the worst-case is often easier to reason about, and therefore is more frequently used as a benchmark for a given algorithm. The process of determining the worst-case and average-case runtimes for a given algorithm can be tricky, since it is usually impossible to run an algorithm on all possible inputs.

The goal of computational complexity is to classify algorithms according to their performances. We will represent the time function T(n) using the “big-O” notation to express an algorithm runtime complexity. For example, the following statement T(n) = O(n2) says that an algorithm has a quadratic time complexity. For any monotonic functions f(n) and g(n) from the positive integers to the positive integers, we say that f(n) = O(g(n)) when there exist constants c > 0 and n0 > 0 such that f(n) ≤ c * g(n), for all n ≥ n0 Intuitively, this means that function f(n) does not grow faster than g(n), or that function g(n) is an upper bound for f(n), for all sufficiently large n→∞

Examples: • 1 = O(n) • n = O(n2) • log(n) = O(n) • 2 n + 1 = O(n) The “big-O” notation is not symmetric: n = O(n2) but n2 ≠ O(n). Exercise. Let us prove n2 + 2 n + 1 = O(n2). We must find such c and n0 that n 2 + 2 n + 1 ≤ c*n2. Let n0=1, then for n ≥ 1 1 + 2 n + n2 ≤ n + 2 n + n2 ≤ n2 + 2 n2 + n 2 = 4 n2 Therefore, c = 4.

Constant Time: O(1) An algorithm is said to run in constant time if it requires the same amount of time regardless of the input size. Examples: • array: accessing any element • fixed-size stack: push and pop methods • fixed-size queue: enqueue and dequeue methods Linear Time: O(n) An algorithm is said to run in linear time if its time execution is directly proportional to the input size, i.e. time grows linearly as input size increases. Examples: • array: linear search, traversing, find minimum • ArrayList: contains method • queue: contains method Logarithmic Time: O(log n) An algorithm is said to run in logarithmic time if its time execution is proportional to the logarithm of the input size. Example: • binary search locate the element a in a sorted (in ascending order) array by first comparing a with the middle element and then (if they are not equal) dividing the array into two subarrays; if a is less than the middle element you repeat the whole procedure in the left subarray, otherwise - in the right subarray. The procedure repeats until a is found or subarray is a zero dimension. Note, log(n) < n, when n→∞. Algorithms that run in O(log n) does not use the whole input. Quadratic Time: O(n2) An algorithm is said to run in quadratic time if its time execution is proportional to the square of the input size. Examples: • bubble sort, selection sort, insertion sort

Definition of “big Omega” We need the notation for the lower bound. A capital omega Ω notation is used in this case. We say that f(n) = Ω(g(n)) when there exist constant c that f(n) ≥ c*g(n) for for all sufficiently large n. Examples • n = Ω(1) • n2 = Ω(n) • n2 = Ω(n log(n)) • 2 n + 1 = O(n)

Definition of “big Theta” To measure the complexity of a particular algorithm, means to find the upper and lower bounds. A new notation is used in this case. We say that f(n) = Θ(g(n)) if and only f(n) = O(g(n)) and f(n) = Ω(g(n)). Examples • 2 n = Θ(n) • n2 + 2 n + 1 = Θ( n2)

Example. Let us consider an algorithm of sequential searching in an array.of size n. Its worst-case runtime complexity is O(n) Its best-case runtime complexity is O(1) Its average case runtime complexity is O(n/2)=O(n)

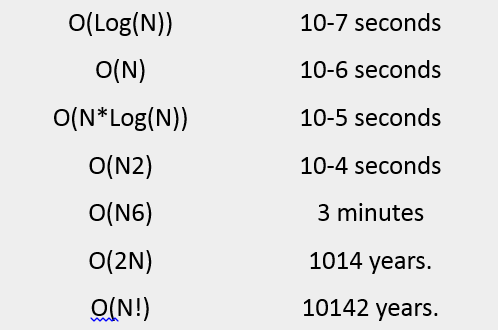

Approximate completion time for algorithms, N = 100

Common Algorithms and their practical usage

This document describes some common algorithms used in the IT industry and their brief explanations.

In Computer Science everything is an instruction and a step by step procedure to perform these instructions is an Algorithm. In other words an algorithm is a brief planning of how the problem in computer science will be solved in general. Therefore it is of major concern in the Computer Science world and almost every aspect of Computer Science need Algorithm. The following list include various algorithms used in Computer Science areas and a brief description about them.

Definition of algorithms Though I’ve defined it a numerous times in my previous articles also, but this time it again needs an exhaustive explanation and a computer science specific proper definition.

In computer systems, an algorithm is basically an instance of logic written in software by software developers to be effective for the intended “target” computer(s) for the target machines to produce output from given input (perhaps null). In simpler words “an algorithm is any well-defined computational procedure that takes some value, or set of values, as input and produces some value, or set of values as output.” Algorithms are like road maps for accomplishing a given, well-defined task. So, a chunk of code that calculates the terms of the Fibonacci sequence is an implementation of a particular algorithm. Even a simple function for adding two numbers is an algorithm in a sense, albeit a simple one.

Now there are many predefined algorithms which are commonly used to solve computers related problems and to devise more complexer algorithms. These algorithms acts as a foundation for making newer and complexer algorithms to solve specific problems.

Like divide and conquer algorithms, greedy approach towards a problem, backtracking, dynamic programming, recursion and randomized algorithms and many more. A brief explanation about each of these algorithms is given below.

Divide and Conquer (D&C) Like Greedy and Dynamic Programming, Divide and Conquer is an algorithmic paradigm. A typical Divide and Conquer algorithm solves a problem using following three steps.

- Divide: Break the given problem into subproblems of same type.

- Conquer: Recursively solve these subproblems

- Combine: Appropriately combine the answers

Some common examples where D&C approach can be applied: – Finding a counterfeit coin using weight balance – Defective chess board – finding the kth smallest element

Some standard algorithms that are Divide and Conquer algorithms. • Binary search is a searching algorithm. In each step, the algorithm compares the input element x with the value of the middle element in array. If the values match, return the index of middle. Otherwise, if x is less than the middle element, then the algorithm recurs for left side of middle element, else recurs for right side of middle element.

• Quick sort is a sorting algorithm. The algorithm picks a pivot element, rearranges the array elements in such a way that all elements smaller than the picked pivot element move to left side of pivot, and all greater elements move to right side. Finally, the algorithm recursively sorts the subarrays on left and right of pivot element.

• Merge Sort is also a sorting algorithm. The algorithm divides the array in two halves, recursively sorts them and finally merges the two sorted halves.